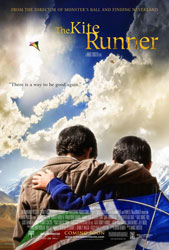

Review of "The Kite Runner" movie

“The Kite Runner” was the first book I read about Afghanistan, before I spent five weeks in Kabul in the summer of 2004. I raced through it, because I generally prefer non-fiction to fiction. The plot depends on a big secret revealed at the end, and that’s just not my cup of tea. To me, the suspense of reading unfolding history seems more honest than a formula melodrama. But the setting of Afghanistan from the hey-days of the 1970s to the Talibs was unique and relevant, especially post-9/11 when interest in Afghanistan mushroomed. “The Kite Runner” pushed a lot of buttons— children, conflict, tragedy, redemption, epiphany— and it charmed millions of readers. It was right out of the headlines, had a huge audience of book clubs, college summer reading lists, and a firm slot on the N.Y. Times bestseller list.

Not being a huge fan of the book, I still really enjoyed the movie, even though sometimes I found it disappointing, maybe because of my “insider’s” view of life in Afghanistan. Though filmed in China, the film’s art departments should be congratulated for imitating many obscure, minute, and accurate details of Kabul street life. The wardrobe and makeup are incredibly realistic, and the packed street scenes approach a travelogue’s reality. The acting and music are generally professional, with many moving high points. The screenplay is as faithful to the book as any movie can be, having to reduce an 8-10 hour story to two.

However, if you haven’t read the book, read it first and then see the movie—it probably will make the plot clearer. And don’t wait for the DVD—see it on a big screen, where the power of the visual feast will be the greatest.

The movie seems to try too hard. Instead of letting the story unfold, the director is a little heavy-handed, trying to cloak the tragedy in a more morose mood than necessary. Everything is dark and brown—clothes, buildings, furniture, books, rugs, vehicles, and actors’ moods. The skies are always cloudy; the air always tinged in ochre. The story rolls out like a familiar dark ritual—another reviewer, unkindly, called it robotic.

The film’s lighting is dull and unimaginative with little range, contrast or depth. The same can be said for most of the by-the-book direction: the camera remains planted in most scenes, cutting from wide shot to close-up to reaction shot, creating a claustrophobic 1940’s-50’s early TV feel. The lead character, Amir, seems more like a metaphor for abject depression than a person. All of this is obviously purposeful, and achieves a unified theme, but an occasional inconsistency would have made it more real.

The extended scenes of the flying kites, which are bright, sassy and full of energy, are the only exception (nudge, nudge) to the dull and dusty atmosphere of a mono-chromatic, single-emotion, two-dimensional culture.

This contrasts with the Afghanistan I know, with its riot of colors in its rugs, paintings, trucks, gardens, architecture, mosques, wedding fests, bazaars, lively conversations and jangly music. The sun nearly always shines in Kabul’s electric blue sky, and the snow-capped mountains create a constantly shifting perspective and depth. The Afghans are quick to smile and laugh and act with grace, warmth, and passion in most situations.

Despite these criticisms (I’d rather call them quirks), the film held my interest firmly throughout its nearly two-hour length, and is an enjoyable, moving must-see for anyone with the slightest interest in Afghanistan.

The most controversial aspects of the film have little to do with the plot, and more to do with current political conditions in Afghanistan. Many believe that the script’s few insults to the Hazara ethnicity would spark riots, if the film were shown in Afghanistan.

Also, some felt that the story’s pivotal sexual assault, which is actually vaguely presented in the movie, would cause a violent reaction. Although political extremists will gladly make a mountain out of any molehill, I don’t think the average Afghan would have a problem with either. They would probably be more upset that they are portrayed as so morose.

But the potential for conflict fuels the controversy-hungry media. Most Afghans will see the movie on pirated DVDs before the movie is a month old, and if you haven’t heard any problems by now, then there probably will be none. Right now, Afghanistan faces much more serious problems from the growing number of nutcases who think the Taliban are a positive force in Afghan culture.

I did respect the honesty displayed in that the U.S. is not portrayed as a paradise for immigrants, where money grows on trees. The gray jumble of Freemont, California’s run-down suburbia and swap-meet culture, and Amir’s proud father’s descent to a crummy convenience store clerk job reflect Kabul’s wartime cheerlessness and sense of loss.

At the end, I was saddened that the negativity and gloom of the evil characters, and the director’s quirky “all the leaves are brown” take on everything would leave a distaste for Afghan society and culture, especially considering that the happy, pastoral finale occurs only after the characters’ escape to America. There is so much more to Afghan culture and history than this sad, somewhat contrived story, which could have happened anywhere. It would be a shame if the millions of people who watch this big movie, will at the end sigh in relief that they don’t have to live on that side of the world.

However, after the movie, I spoke with the lady sitting next to me, who had just read the book, and loved the movie. When I told her I’d spent some time in Kabul, she replied, “Oh, I’d love to go there!” Didn’t it seem to be too grim and dangerous and mean? “Not at all, it was fascinating,” she said. “Well then you should go, don’t be afraid of it,” I said with a relieved smile.

“The Kite Runner” is a good first step, that will open a window. I look forward to the quintessential Afghan production on the level of “Dr. Zhivago” or “Lawrence of Arabia” filmed on Afghan soil.

One final note,; the movie theater was packed at the 4:30 pm New Year’s Day show in Charlotte, NC, where “The Kite Runner” is on two screens. It’s being treated as a borderline “art film,” as it probably should be, due to its talkiness and general lack of extensive sex, violence, drugs, and guns that are the hallmarks of Hollywood. Most critics are lukewarm, but the built-in audience of those who read the book are making a respectable box office draw. The movie should be around for a while and be a moving experience for most. Don’t miss it.

Poems for the Hazara

The Anthology of 125 Internationally Recognized Poets From 68 Countries Dedicated to the Hazara

Order Now